| interviews | the writting on the wall | murals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| previous exhibition | next exhibition |

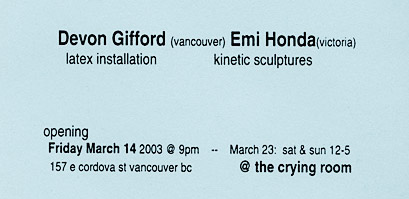

SYNTHETIC LANDSCAPES.........................................Devon Gifford and Emi Honda, March 2003 |

|

|

SYNTHETIC LANDSCAPES Opening March 14, 2003 |

|

|

Devon Gifford, latex installation |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

|

|

|

Devon Gifford, latex installation (detail) |

|

|

|

Devon Gifford, latex installation (detail) |

|

|

|

Devon Gifford, latex installation (detail) |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages

|

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

|

|

|

Emi Honda, kinetic sculptural collages |

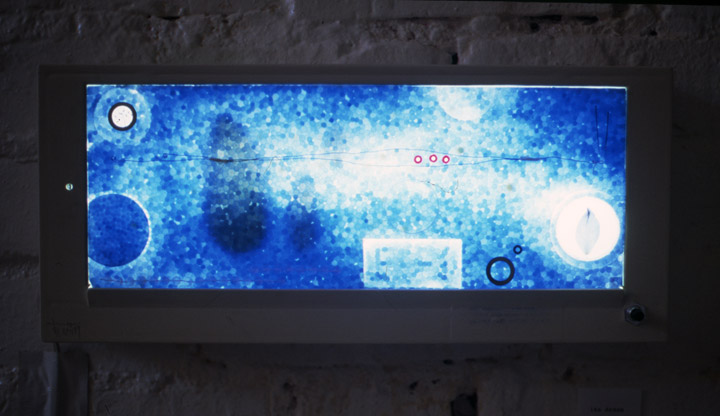

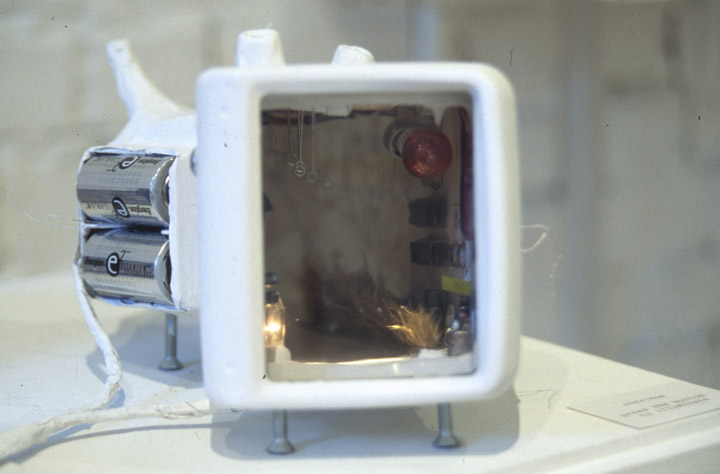

|

| Synthetic landscapes explores the widening gap between nature and modern life. The pairing of work between Devon Gifford and Emi Honda illuminates the contrast between macro and micro perspectives, and the relationship between beauty and the abject. Both bodies of work intimate qualities that engage with the viewers tactile urges to investigate and explore the landscape, and objects around them. Both Gifford and Honda use synthetic “man-made” materials to describe the natural, or their individual perception of nature and utopias that imagination unfolds. At times, and specifically within Gifford’s work, the emulation of defects becomes the central “highlight” of the landscape. Combined, these work question the space where the landscape “settles”, weather it be on macro details of apparent flaws or within micro views of futuristic underwater fields. Both artists explore landscapes as a subject, suggesting that a landscape entails that which surrounds us which is constantly shifting, specifically as a result of modernization. A landscape can function as a tiny object or screen that we gaze into, our architectural and natural surroundings, as well as the surface of our own skin. Through re-inventing and reconstructing surfaces and environments derived from nature Gifford and Honda create this perceptual shift and bring into question our relationship to our surroundings and the significance with them. Gifford suggests to bodies as a landscape that surrounds us, and Honda creates small plastic environments to gaze into, and upon. The micro/macro dynamic between these two installations allows for a perceptual shift. Gifford’s landscape is an enlarged imitation of a relatively small surface of skin, whereas Honda’s work contains condensed micro landscape with a futurist esthetic. The work within Synthetic Landscapes draws attention to the interplay and consequences that technology has, and will have on our surrounding landscapes. The landscape has always been a political battleground for natural resources and power. Over the last one hundred years we have become increasingly aware of the significant and irreversible affect that modern technology has had on our natural environments. The ironic result of this is modern cultures innate response to redeem these growing problems caused by technological development in our natural environments through technological means. Perhaps as we are unable, or too stubborn to currently deal with these issues fully, or perhaps these puzzling issues are simply unpleasant and temporarily avoidable. Gifford’s installation, Landscape No.2, is of a narrow latex band painted on the wall. The installation begins at the far end of the gallery and stretches straight across the wall commencing on the front door, with a flap of latex by-passing the corner of the door and the wall. This corner flap references a joint and skin’s elastic function of surface as mechanical architecture bends and extends. Gifford’s latex surfaces imitate the surface of human skin under a microscope, with patches of hair and sparse pimples, blackheads, boils and ingrown hairs. Gifford’s exploration of skin challenges the viewer to confront natural abject features that are often discomforting and predominantly concealed within western culture, specifically in the media. Gifford celebrates these flaws through her well crafted use of the material and tension created through the viewer wrestles with urges to remove or “pop” these blemishes. Gifford’s work neutralizes the abject qualities of her subject through her slick presentation and sterile materials as she emulates these pockets of oil and dirt. Her work compares to the work of Nicola Costantino, a contemporary Argentinean artist living a working in Buenos Aires. Costantino creates patterned synthetic fabric, molded from human bumps and crevices with sexual connections such as, the belly button, nipples, and sphincter, and from this material Costantino creates fashion garments such purses, shoes and jackets. Both Gifford and Costantino emulate skin and remove it from it’s natural surface, and challenge it’s meaning through this disposition and deconstruction of material. Emi Honda’s work consists of eight small kinetic sculptural collages. Her work is a mixture of landscapes built from old toys with electrical parts for aesthetic, cultural and functional purposes. Honda’s landscapes are dense yet delicate. Her work presents synthetic materials that imitate and form futuristic environments that also reference natural world. Honda’s work reveals her cultural background, as synthetic landscapes have become connected with the identity of contemporary Japanese culture. Honda’s work fits in stride with the work of Mariko Mori, a significant contemporary Japanese artist who explores the bounds of technology within her production and who also generates a dialogue between the disconnection and reinvention that people have regarding natural and synthetic environments. However, contrary to the relating dialogue between these two artists, the form of production, materials and size is drastically different; Honda’s work is small and re-invents the old as new, whereas Mori works with grand and cutting edge technology. Both Honda and Gifford’s reflect the influence of their own cultural background. Honda’s work re-interprets various technologies as esthetically pleasing, futuristic sensory toys. This futurist esthetic is commonly associated with Japanese culture, as Japan remains one of the leading centre’s, embracing new methods and forms of technological adaptation and experimentation. Japanese culture in the last few decades has delved into the new and clean esthetic of modern technology, welcoming the cyborg -- the union of man and technology. This concept and esthetic has been commonly borrowed and influenced by anime and Manga, Japanese animation and comics. This synthetic or plastic esthetic has become increasingly popular specifically to younger generations as we succeeded the 20th century and delve into the 21st century. Contemporary Japan has developed an international reputation for it’s futuristic style, simulated environments, and technological consumption. Currently Japan is undergoing a distinct split from ancient Japanese culture into new methods and icons of cultural representation, this has created pockets of generation clashes between older and new generations. This new form of cultural representation involves a borrowing of styles from other cultures. Japanese culture has developed an interesting hybrid style; as western culture has seeped into Japanese culture over the last 50 years, it has steadily developed an original mix of older Japanese styles with western influences. [ a concept discusses in Shoichi Aoki’s introduction to Fruits, a contemporary photography book on cutting edge fashions from the Harajuku district in Toyko Japan, p.1, 2001] . Honda re-uses discarded electrical parts and synthetic toys creating mysterious, beautiful, precious environments. Despite the plastic, futuristic and unworldly look of these sculptures, they all reference common cultural objects and environments, attributing organic qualities to materials that are commonly viewed as inorganic. Honda’s work in Synthetic Landscapes consists of eight different pieces, divided into three different groupings. Her most recent work includes four various reconstructed snow-globes of various shapes. These pieces are rather small, standing four to six inches in height and a few inches in diameter, are elegantly constructed. Honda has disassembled found snow-globes, evacuated the initial form and created new landscapes. She has titled these pieces planet S, M, N and L, suggesting that these underwater environments are in-fact other worlds that confortably rest in the palm of your hand. Within these tiny snow-globes she has created a white base where plastic beaded string grows from, as well as, plastic plants, Christmas lights, and other odd plastic bits. Some of the snow-globes have a music wind on the bottom, one has sparkles in it that snows when shaken and two have different coloured water, one is blue, another red, and the other two are clear. The colours that Honda has uses are simple, with no more than two or three per globe, and the objects used are elaborate yet concisely placed. Botanical garden and Corridor, are slightly larger than the snow-globes but are objects with a singular magnified viewing screen similar an illuminating slide boxes, opposed to the transparent, 3 dimensional viewing of her planets. Within these corridors and through these magnified screens Honda has places an assortment of objects similar to the planets, yet with a greater diversity of material, combining plastic, dried organic material and a strong presence of metal and electrical parts. Within Corridor is a scientific drawing of a man and a woman, the only presence of the human figure within Honda’s work. This appearance of human representation draws a link between the material of the work and the natural landscape that it suggests. They function as a reference towards our current cultural abilities to desect the landscape and recreate it; within Honda’s work things are not always as they seem, such as, the end of a guitar string gives the impression of sprouting upwards like a blooming flower. Finally, the last two pieces within Honda’s body of work are Environmental TV and Ika Dream. Both of these pieces are twice the size as the rest of her work and presented as light boxes. Environmental TV is a kinetic sculpture of a small plastic toy TV, with lights inside and a channel that controls music, and another switch that activates a rotating diorama. Within the diorama is paper cut outs of flowers, bunnies and chicks (as in birds), make a slow crawl across the screen as the bells ring a child-like jingle. The fine attention to detail outlines a stark contrast between the mental state and motivation behind the creation of these objects as playful and beautiful yet relatively useless, compared with the lethargic and numbing effect that we commonly associate with “functional” televisions. Ika Dream is a 2 dimensional wall piece, of a thin layer of blue foam illuminated, and framed with a with a small white border. On the surface and behind the foam Honda has sparsely placed objets such as red beads and two leaves, one clearly exposed behind a clear circular covering and the other silhouetted behind the blue foam. This piece in particular has a clean, and sterile look about it, yet it still contained the delicate playful beauty found in her other work. The blue Styrofoam abstracted from common placement and illuminated transforms the material and produces a hyper-real(3) surface of pleasing layers of glowing tiny blue bubbles. Honda has the ability to find lost and disposed gems and transform them into precious objects. Honda’s cleaver use of material references the disposable attitudes within some, perhaps late capitalist cultures, as they follow “Brave New World” (4) slogans such as; “Ending is better than mending, the more stitches the less riches”(44). This reminds the viewer that their is just as much to be found as their is to be made. As a compliment and contrast to Honda’s work, Gifford’s installation entails a slick minimalist landscape of human skin, with subtle yet jarring details. From a western perspective, human skin presented as a landscape points towards the body as a surface for pruning. The media produces the majority of western society’s cultural production, which often incurs images of the body as a refined commodity. This social construction and cognitive influence helps to sustain a successful consumer culture which is the final aim of the media. This system ineffect, creates unachievable cultural expectations regarding the body as a natural landscape that must be tamed. Landscape No.2 references the reality and intimacy that occurs when individuals are in a position to view a body on a macro scale, in viewing ranges that can detect natural flaws and perfection’s. It is often these flaws that give the viewer a sense of reality, and challenges individual’s level of acceptance; in relation to intimacy and affection, we are often in a position where we must accept an individual and their body in it’s entirety, specifically, pertaining to perfection’s and flaws. The surface blemishes that Gifford emulates also plays with common animal instinct’s to groom and “clean” one-another; an action that involves trust, and often occurs within intimate relationships. If the viewer is unable to accept these human “imperfections”, their lies a risk of perpetual dissatisfaction as our expectations succeed the natural possibilities of the skin. Inversely, there also exists the phenomenon of satisfaction that we experience when we discover a flaw on a seemingly perfect surface, this allows the “perfect” individual to become more “real”. Both Gifford and Honda challenge the cultural meaning of the landscape as a construct. They both investigate and how one settles a landscape, how do you interpret and understand “landscapes” in current society, and what meaning and impression do you derive from it? There is no doubt that landscapes are becoming a highly charged politicized subject, as we see the passing of the last century, stretching throughout modernism, from the age of industrialization to the information and technological revolution. “Landscapes” are slowly transforming from an object to a subject, as W.J.T. Mitchell mentions in his current book “Landscape and Power”. Mitchell aims to, “change ‘landscape’ from a noun to a verb...ask(ing) that we think of landscape, not as an object to be seen or a text to be read, but as a process by which social and subjective identities are formed” (1). As years pass we are left with few natural spaces, free from political scars that we can escape into. As a result of this we are driven to create these utopia’s and places of escape ourselves. Often they entail a synthetic cleanness, free of the uncontrollable disruptances of nature, often, but not always. At other times, for instance in Gifford’s work we see an enbracment with the abject, to accept what we can not always control, this functions as a method of empowering ourselves and allowing ourselves to make peace with the natural morality of our own skin. Both works have a slightly eerie reference to concept or looming era of Posthuman. The use of synthetics in relation to the surface of skin, environments and landscapes suggests towards the lure and appeal of plastic, as well towards the breaking down of border’s between the “real” and “simulated” as Jean Baudrillard, a postmodern theorist mentions in his essay “Simulations”; “Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal”(203). Both Gifford and Honda demonstrate a sense of command regarding craftsmanship and material. In union with the elegant and simplified presentation, both artists display their ability to process and emulate fine detail. This aspect relates to both the landscape as a general view, or a specific point of interest. Mitchell discusses this specifics of the view of a landscape in Landscape and Power, “It is generally the ‘overlooked’, not the “looked at”, and it can be quite difficult to specify what exactly it means to say that one is ‘looking at the landscape’”(vii). Within Synthetic Landscape meaning is produced through the artists focus on details that are often overlooked, or perhaps scarcely achieve, which leads the viewer to appreciate that in-fact, less is often more, as we all risk various levels of over-stimulation in relation to cultural production and urban environment. |

|